The Titan implosion was unprecedented in submersible diving history

Five people died when the Titan submersible imploded during its descent to the wreck of the Titanic last week. Some commentators have described deep-diving submersibles as inherently risky and experimental (e.g. Boris Johnson in his Daily Mail opinion column), but their actual history shows that is far from the case.

Since the first bathysphere dives in the early 1930s, human-occupied vehicles have taken many more people into the deep ocean than the number of people who have been into space, with none previously experiencing a catastrophic hull failure and far fewer fatalities overall than space travel. The investigation of the Titan will now seek to understand why it was such an outlier.

Deep-diving submersibles are smaller than traditional submarines, and unlike submarines they are launched and recovered from a surface support ship. Although submarines have suffered implosions when damage or systems failures have caused them to sink beyond their much shallower depth limits, no submersible had imploded before under the huge pressures of the deep ocean.

Track record of submersible safety

Before the Titan, the only fatal incidents involving the occupants of submersibles occurred in the 1970s in shallow water. Fumes from an electrical fire overcame the occupants of a Japanese tethered diving bell at around 10 metres deep in 1974. Prior to that, the Johnson Sealink submersible became entangled on a shipwreck at 110 metres deep in 1973, and two of its four occupants died from carbon dioxide poisoning before it was recovered. And in 1970 the Nekton Beta submersible was salvaging a sunken powerboat, which broke free from its lifting line and collided with the submersible, causing a leak that drowned one of the occupants.

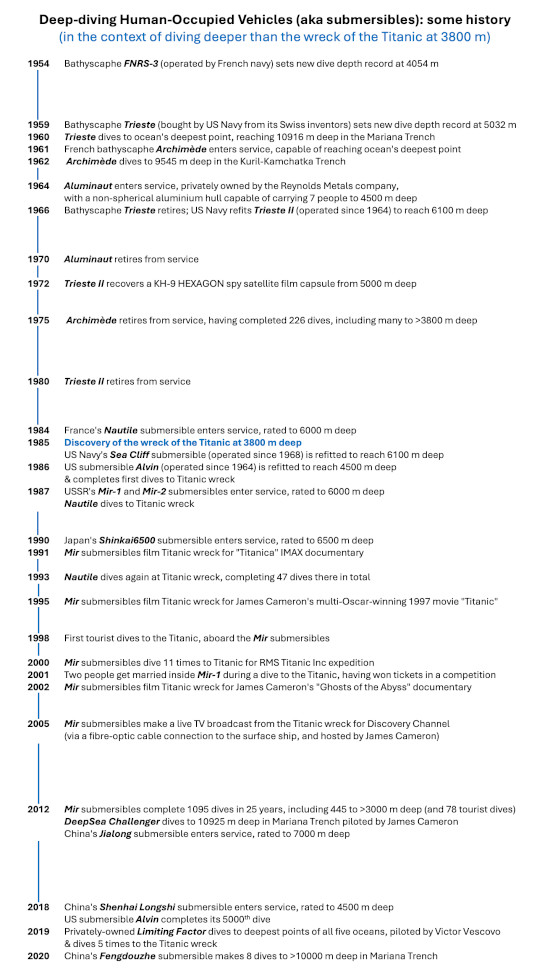

When the wreck of the Titanic was discovered at 3800 metres deep in 1985, submersibles had already been diving to greater depths than that for several decades. The first to do so was the bathyscaphe FNRS-3, which set a record at 4050 metres deep in 1954, and there have been at least 16 submersibles that have repeatedly taken people deeper than the Titanic in the past 69 years. The French bathyscaphe Archimède, for example, made 226 dives between 1961 and 1975, including descents to more than 9000 metres deep in ocean trenches.

Track record of submersible dives to the Titanic

The US submersible Alvin made the first dives to investigate the Titanic in July 1986, followed by the French submersible Nautile in 1987. Nautile returned in 1993 and dived to the wreck 47 times in total. In 1991 the two Russian Mir submersibles filmed the Titanic for the IMAX documentary Titanica directed by Stephen Low, and over the next 14 years the Mir submersibles dived to the wreck on more expeditions than any other vehicles, including filming in 1995 for James Cameron’s movie Titanic and in 2002 for his 3D IMAX documentary Ghosts of the Abyss.

Mir submersible being launched

The Mir submersibles were used for the first tourist dives to the Titanic, which began in 1998 and cost 32,000 US dollars at that time, equivalent to around 69,000 US dollars today. Two people got married aboard Mir-1 while it was diving on the bow of the Titanic in 2001, having won their dive tickets in a competition. On their final dives to the Titanic in 2005, the Mir submersibles also filmed a live TV programme from the wreck, relaying images via a fibre-optic tether to their support ship and then ashore by satellite. James Cameron presented the show, Discovery Channel’s "Last Mysteries of the Titanic", from inside Mir-2 as part of the first broadcast from such a depth.

Submersibles currently capable of reaching the Titanic

The Mir submersibles are now museum exhibits, and there are currently seven submersibles (and one "submarine") in service that can reach the depth of the Titanic and beyond. Six of them are owned by governments and used for deep-sea science.

The US submersible Alvin has completed more than 5000 dives and is now certified to 6500 metres deep after a recent upgrade. Japan’s Shinkai6500 can also operate at 6500 metres deep, while France’s Nautile is rated to 6000 metres, and there are three Chinese deep-diving submersibles: Jiaolong (7000 metres), Shenhai Longshi (4500 metres), and Fengdouzhe, which dived 8 times to more than 10,000 metres deep in the Mariana Trench in November 2020.

There's also Russia's Losharik submarine (larger than a submersible, and not launched from a surface support ship), reportedly capable of diving to 6000 metres with its multi-sphere titanium hull design.

There is one very deep-diving submersible in private ownership: the Limiting Factor was built by Triton Submarines for billionaire Victor Vescovo to pilot to the deepest point in all five oceans in 2019, which has since dived in more than a dozen deep-ocean trenches, including repeated dives to ocean’s deepest point. Limiting Factor also dived to the Titanic five times in 2019. In 2022 Vescovo sold it to the Inkfish research organisation founded by billionaire Gabe Newell, and it has since been renamed the Bakunawa.

What was different about the Titan?

All of the current submersibles than can reach the depth of the Titanic enclose their occupants in a spherical metal hull, as that shape helps to distribute pressure evenly across its surface. Those submersibles can only accommodate two or three people, as a larger spherical hull would be too big and heavy to launch and recover easily from a support ship.

Russia's Losharik submarine is an exception with its larger size, but it still effectively uses spherical geometry for its hull, which consists of multiple joined titanium spheres.

The Titan had a tubular-shaped hull, splitting the traditional sphere and inserting a carbon-fibre tube between its halves to make room for five occupants. That design concept - hemisphere "end caps" with a cylindrical section between them - has been used in shallower-diving submersibles. The Perry series of submersibles were built with that design, including the Antipodes that has acrylic end caps (and was previously owned by OceanGate), and the Nekton series. But those submersibles are only rated ~300 metres (1000 feet).

Hull shape isn't the only consideration, however, in investigating what happened to the Titan. The Aluminaut submersible of the 1960s, which was capable of diving to 4500 metres deep, had an aluminium hull (17 cm thick) with an overall tubular shape (16 m long) that could carry seven people. So the investigation will also consider the materials used in the hull of the Titan, including the carbon fibre that had not been used for that purpose before, and how the two titanium hemispheres and carbon-fibre tube section of the Titan's hull were joined together.

Carbon-fibre in submersible design

In the early 2000s, the DeepFlight Challenger submersible was developed by Graham Hawkes, who is a hugely experienced submersible designer (I've dived the Deep Rover 2, which is one of the many submersibles that he has created).

Hawkes's goal was to create a vehicle that could reach the ocean's deepest point (>10,000 m), and DeepFlight Challenger was very different in principle to other submersibles, operating like an "underwater aeroplane" (and images of the DeepFlight concept were included in the titles sequence of the TV series Star Trek: Enterprise).

The hull of DeepFlight Challenger was designed for a single occupant lying down, and consisted of a carbon-fibre tube with two end-caps, which is similar to the Titan in those aspects.

But the project stalled, following the death of backer Steve Fossett in a plane crash. Richard Branson then explored a "Virgin Oceanic" venture to revive the project, but interest waned after James Cameron reached the Challenger Deep in his DeepSea Challenger submersible in 2012.

Consequently, the tubular carbon-fibre hull of DeepFlight Challenger never actually dived to great depth, as far as I am aware - and carbon-fibre therefore remained an experimental material for submersible design, prior to its use in the Titan.

Never before, never again

In 2013 I dived aboard Japan’s Shinkai6500 submersible to study undersea hot springs at 5000 metres deep on the ocean floor, and I would dive in that vehicle again to such depths if I had the opportunity – not as any sort of risk-taking adventurer, but as a scientist safely going to work. By analysing debris from the seafloor, the investigation of what happened to the Titan needs to examine why it is such an exception in the safety record of deep-diving submersibles.

(This article was subsequently published in edited form in The Conversation and other media outlets)

Jon Copley, June 2023

| Previous | Index | Next |