How much of the deep sea have humans seen (and how much have I seen)?

A new paper by Dr Katy Croff Bell and colleagues does a great job compiling dive data from deep-sea vehicles to estimate the percentage of the deep ocean floor that has been visually surveyed.

It's around 0.001% (one thousandth of one percent), which is an area about the size of the state of Rhode Island (or about one-tenth the area of Belgium if you prefer).

The paper's authors acknowledge that's an underestimate, as not all the dives by vehicles and camera systems since the 1950s have been suitably archived to include in their analysis. But their estimate won't be out by an order-of-magnitude.

I was pleased to be a reviewer for the paper (having previously made a wild guestimate of ~0.005% in one of my popular-science books, but not from the careful quantitative basis of this work).

Unlike some of its media coverage, the paper avoids describing the 0.001% area as "explored", because that's a meaningless term unless you define the end-point for "explored" (e.g. seen just once?), as I've explored (ha ha!) in a previous blog.

The paper also shows a decline from deep-sea exploration in the "high seas" to more focused in the Exclusive Economic Zones of countries (usually within 200 nautical miles of their coastlines) since the 1980s.

That's perhaps understandable, as nations focus their resources on understanding the deep sea under their jurisdiction (EEZs being recognised since UNCLOS - the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea - was agreed in the early 1980s).

But it highlights the important challenges for understanding processes in the majority of our deep-ocean planet that lies beyond those boundaries (as I also recall from my time as Co-Chair of the InterRidge initative for international cooperation in research at mid-ocean ridges).

How much have I seen?

For a bit of fun, using the same basis as the paper, I had a go at estimating how much of the deep-ocean floor I've seen (working from number of expeditions, average number of HOV or ROV dives per expedition, and recognising that some dives visited the same location etc).

It's probably about 1.5 km2. That's ~0.000005% of the deep-sea floor. About the same area as where I run in the New Forest.

Area in the New Forest of the UK approx 1.5 km2

A two-hundred-thousandth of one percent of the deep ocean. And an equivalent area on land that I can run around in less than 45 minutes. In a career (albeit it a very meandering one!) as a deep-sea scientist across three decades.

But that ~1.5 km2 is about half a percent (one two-hundreth) of the estimated total that humans have seen, which is perhaps not too shabby for one person. And what that 1.5 km2 contains has been incredible.

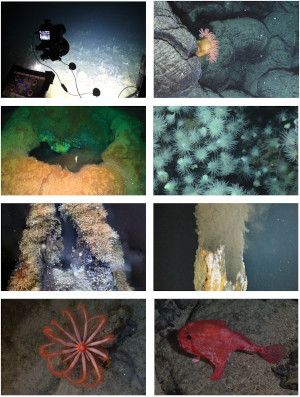

Spires of deep-sea vents in the five major regions of the global ocean, including the world's deepest known ones. A brine lake at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. The steep slopes of undersea mountains around Antarctica. Mounds of bizarre methane ice poking out of the seafloor ~3 km deep in the Arctic.

And more than 30 species of animals that no human eye had seen before, with adaptations that have since inspired new materials for sound and heat insulation, and better ways to make solar panels.

What's in the next ~1.5 km2, I wonder?

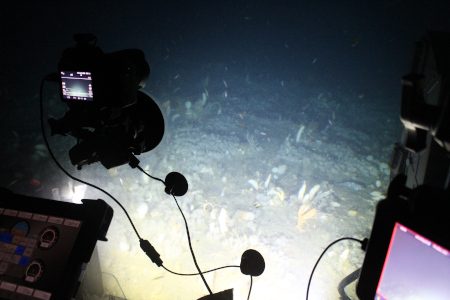

If I were a billionaire philanthropist wanting make a real dent in deep-ocean exploration, then rather than building a superyacht research ship, I'd consider backing the development and growth of low-cost technologies that enable more communities around the world to explore the deep. Technology like the Maka Niu camera system also developed by Katy and colleagues in the Ocean Discovery League.

I think the two most important questions now in deep-ocean exploration are not purely scientific ones, but rather "for what purpose?" and "for whose benefit?". And to explore the deep ocean to benefit all of us, we need to build a more inclusive society, in science and beyond.

Jon Copley, May 2025

| Previous | Index | Next |